Welcome to the very first volume of The Little Red Notebook. It’s been great to see so many of you sign up already. If you like what you read here, please forward it on to anyone you think might enjoy it.

I’ve been reading New York Times reporter Kashmir Hill’s new book on Clearview AI. With just a single snapshot of your face, the Clearview app can reveal who you are, where you work, where you’ve been and whatever you’ve said online. It’s already been used by police forces and billionaires alike.

“If it became widely available, Clearview could create a culture of justified paranoia. It would be as if we were all celebrities with famous faces. We could no longer trust that when we bought condoms, pregnancy tests, or hemorrhoid cream with cash at the pharmacy, we did so anonymously. A sensitive conversation over dinner in a restaurant could be tied back to us by a person seated nearby. Gossip casually relayed over the phone while walking down the street could get blasted out by a stranger on Twitter with your name as the source. A person you thoughtlessly offended in a store or cut off in traffic could snap a photo of your face, find out your name, and write horrible things about you online in an attempt to destroy your reputation.”

Kashmir Hill, ‘Your Face Belongs to Us: The Secretive Startup Dismantling Your Privacy”

Forget Big Brother - facial recognition technology has the capacity to turn us all into Little Brother too.

This book landed in my lap at the right time. I’ve been thinking about privacy a lot ever since I gave two multibillion-dollar corporations my DNA. (The corporations were AncestryDNA and 23andMe, and it was for a thing - my new series for BBC Sounds and Radio 4, which is out in September.)

There’s now a critical mass of data about who we are floating in the cloud, waiting to be scraped by AI or scrutinised by anyone inclined to investigate us. Even if we haven’t uploaded it ourselves, our friends, relatives, colleagues, acquaintances and even people we pass in the street may have shared enough information (pictures, text, locations and genetic code) that includes us for our anonymity to be blown forever. We may have already stumbled into the post-privacy age, whether we like it or not.

Anyway, the book is brilliant and terrifying, and so is the prospect of getting my DNA results, which should be in my inbox sometime next week. Wish me luck.

Why is UK journalism short on long-reads? …asks Charles Baker in a medium-length article for Press Gazette. Here’s the tl;dr version of that article: editors say there’s a very small talent pool of writers in the UK who can actually pull them off, and writers say British publications don’t pay enough.

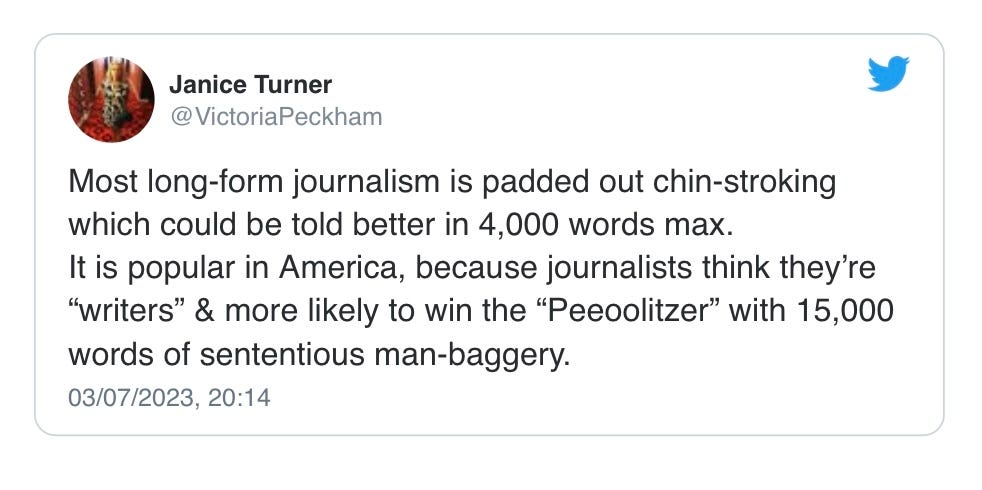

Baker’s piece was much shared on Twitter. It inspired this tweet from Times columnist Janice Turner:

…which I emailed to myself as a note to remind me to write about it here, but the tweet had been deleted by the time I clicked on it the next morning. Maybe that’s wise. Some things need more words than a tweet allows to explain properly, after all.

Quality long form journalism is difficult. The reporting, writing and editing take ages, and much of the work doesn’t end up visible on the page. Many long form writers do their own transcription, which helps with mastering your material, but it’s laborious: I could have an exclusive interview with God and I’d still find the transcribing fist-gnawingly dull. But it’s worth it in the end. (I hope.)

Some of the best bits of journalism I’ve ever read have been American long form pieces, and yes, some did go on to win Peeoolitzers, like Gene Weingarten’s unforgettable piece on parents who forget their children in the backseat of their cars. See also anything by Patrick Radden Keefe, but particularly this piece on Amy Bishop, the University of Alabama academic who was also a mass shooter. We are getting good at it here in the UK - read Sophie Elmhirst’s writing and you’ll feel encouraged - but to produce articles of value, we need to value those articles more, and invest in them.

Other things that have caught my eye:

The Past Present Future podcast on who owns outer space, and how our new-found ability to stop asteroids from colliding with earth might paradoxically lead to the end of mankind

The three-part Arnold Schwarzenegger doc series on Netflix, which made me a bit depressed about a future where only hagiographies, rubber stamped by their celebrity subjects, get commissioned and made (see also the Wham! doc, the Pamela Anderson doc, and pretty much any other biographical doc featuring a still-alive famous person)

…but it led me to waste an enjoyable 20 minutes and several of the 600 tweets Elon Musk is allowing me to read in a day on this thread, about how Terminator 2 was made. (It came out 32 years ago this week)

I ended the week feeling hopeful, after speaking to Sunday Times Science Editor Ben Spencer for the Stories of Our Times podcast. Ben told me how phages - which sound like something straight out of the Terminator - are poised to save humanity once antibiotics stop working

Congratulations on reading to the end of LRN No.1. I’ve tried to keep this short but, as a long form journalist, this is not my forte. Do reply and comment and tell me what you liked about it, what you’d like to see, whether you want more pictures of my chin, etc.

Clearveiw is worrying

A Superb Read