If you value life, it can’t be priceless. If we were willing to devote unlimited resources to saving certain lives, then others would die from lack of food or medicine as a result. The moment we stop being happy to pay to save a life is when we reveal the price we are comfortable paying for one. But where you stop is very much a matter for debate.

There was one approach to calculating the price of life that never made it into my book: the value of statistical life. But it deserves a mention here, because tens of thousands of people are probably alive because of it.

Until 1982, there was nothing to compel businesses in the US to label chemicals like asbestos or hydrochloric acid as hazardous, or to warn people they might explode if they lit a cigarette while using acetone paint stripper. The US’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) estimated that 4,750 lives could be saved by labelling dangerous substances.

At that time, economists used a “cost of death” figure when trying to determine which safety interventions were good value, made up of the average future income lost by someone who died prematurely. The going rate in 1982 was $300,000 per death, meaning $1.4bn could be saved by labelling the substances. But the estimated cost of making the labels was $2bn. Which meant it wasn’t worth doing.

The Harvard economist Kip Viscusi said the cost of death figure was inadequate; according to that approach, unemployed people had no value at all, and life should be worth far more than death, he argued. Instead, Viscusi said they needed to be working with the “value of a statistical life”, which could be determined from looking at the premium people in dangerous jobs expect to be paid to compensate for the risk to their lives.

In 1982, there was a 1 in 10,000 chance of dying at work, and he found that workers in hazardous jobs earned an extra $300 to $400 a year compared to equivalent work in safer jobs. For every life lost, 10,000 people get $300. That put the price of life at $300 x 10,000, which is $3 million.

If 4,750 lives could be saved by changing the labels, and the price of life was $3 million, that meant labelling hazardous substances would actually save $14 billion. It now looked like good value for money. OSHA gave the labels the green light.

Viscusi’s value of a statistical life stuck, and is still regularly used in moral and policy decision-making in the US. (He puts it at $10 million in today’s prices). But it doesn’t fully account for the price of life. It doesn’t factor in how a person dies, or at what stage of life. Did they have the rest of their lives ahead of them? It only considers the value of American lives. It doesn’t include the cost of losing someone you love and being bereaved. And the value of a statistical life only looks at the price of saving lives. What about the cost of creating life? Compensation for our loved ones if our lives are taken? What is the cost of a human body?

If you’re interested in all that, you need to read the book.

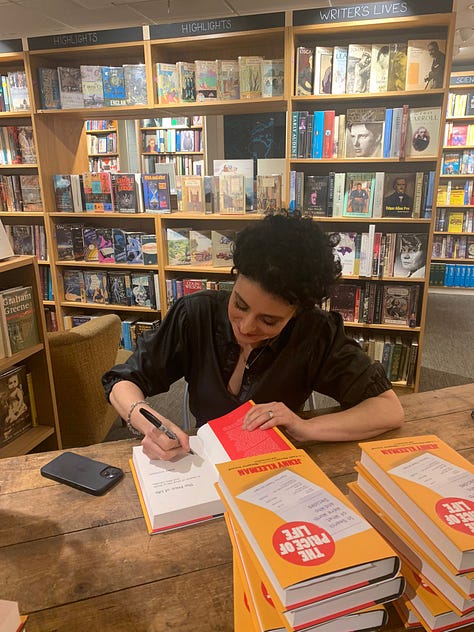

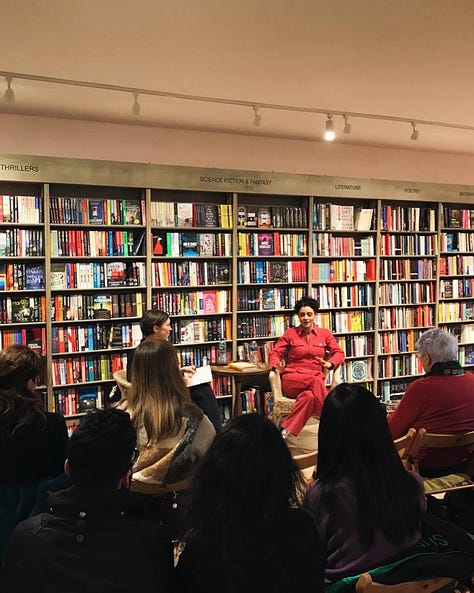

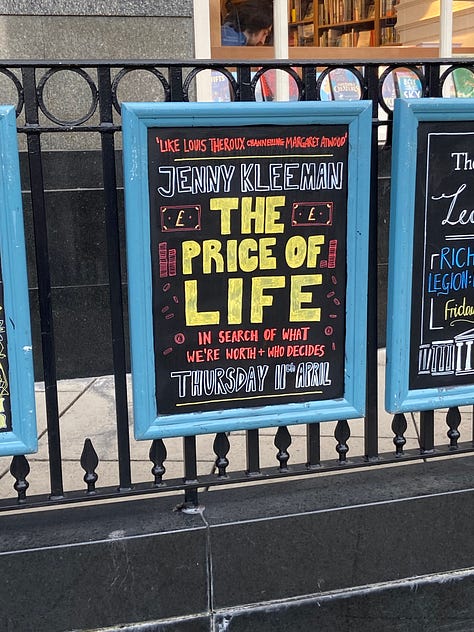

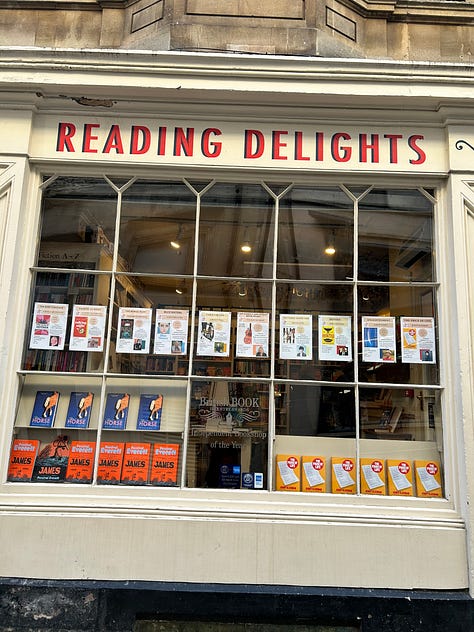

Some highlights of my life on the road over the past few weeks. Meeting people has been the best part of writing the book.

I have plenty more dates coming up - from Falmouth to Bestival to How The Light Gets In to the Nevill Holt Festival and plenty more, including several in London. Watch this space.

Things that have caught my eyes and ears:

Francisco Garcia’s absorbing Guardian Long Read about how a boy he knew from primary school ended up being convicted of human trafficking

Like everyone else, I watched Baby Reindeer, but I watched it early, and before there were spoilers everywhere, so I found it genuinely shocking. Agree with Hugo Rifkind that it’s probably a couple of episodes too long. But it has lingered in my mind for days

Can’t get enough of the Merlin Bird app (hat tip to my sister Nicole), which is essentially Shazam for birds, and has totally changed my perception of the world

Very grateful for all your Disney+ recommendations. No less than three of you said I should watch Dopesick, which I am working through, feeling utterly furious in all the right ways.